The United States academic Kristen Ghodsee is convinced that women in the Eastern Bloc had a more fulfilled love-life — and significantly more equal rights. Can capitalism take that lying down?

By Susan Vahabzadeh

For very few people in a totalitarian state did politics dominate the every day. It might be difficult in North Korea to forget even for a second that one is in North Korea. But in the DDR the everyday was often simply just that — the everyday. And it had, from a feminist standpoint, definite advantages. In Germany, people are reasonably aware that women from the East missed gender equality in the West in the 90s. For them, child care was a matter of course and financial independence was the norm. Even women who grew up in the DDR and have nothing good to say about it sometimes suffer from a sort of feminist Ostalgie.

In this country, it is difficult to discuss this without exposing yourself to the suspicion that you would thereby be defending the Stasi. Kristen Ghodsee, professor of Eastern Europe at Pennsylvania University, knows that it is even more difficult in America — in the foreword of her book "Why Women Have Better Sex under Socialism", she excuses herself for having decided on a nuanced inspection. Her book is only incidentally about sex — that is the reward when relationships are no longer decided as transactions.

Patriarchy begins to crumble when it can no longer rely on capitalism – this thesis is also pursued by the British author Laurie Penny; but Ghodsee argues historically, and sometimes the other way around. Penny is of the opinion that capitalism also exploits most men. Ghodsee comes to the conclusion that it makes it harder for them to be loved — because they have been degraded into a credit card on two legs.

Did women under socialism have better sex? Yes, thinks Ghodsee; there were studies about it in the Eastern Bloc, and they seem plausible to her. A man complained to her that under socialism one "had to be interesting." Providers were not so urgently sought. According to Ghodsee, that falls out of the theory of sexual economics, which says that we all see sexual relationships as a kind of trade, in which the man is almost always the buyer. Sex for provisions. That is, according to the theory, the incentive for men to achieve something. A job is there to make them more attractive to a woman. Or several.

A love affair functions like an exchange market. Except that both partners are independent.

Is that actually so? Ghodsee can only substantiate this in anecdotes, and one can certainly not generalize. But it would suffice if the prevailing system advantages love affairs as transactions. A love affair which does not function as an exchange market thus presupposes that both partners are economically independent. This is by no means the rule in the West. And also no longer in the Eastern Bloc.

Ghodsee only considers a particular time period, namely that since the Industrial Revolution. One can argue about when exactly the simple activity of trade became capitalism. But the representation of the housewife, who cooks the food at home and then sews the collar of her favorite dress, is relatively new. And: even the housewife works, but she does it for free. Not working at all was always reserved only for wives of very rich men.

You don't need to follow Friedrich Engels and persuade yourself that matriarchy was the normal form of communal life before capitalism. But in agrarian societies women always had their share of fieldwork to do — thus even economic dependence was shared differently, because economic survival for both partners was at stake. Seen thus, the economic dependence Ghodsee complains about is perhaps not at all a natural state.

Ghodsee's diagnosis of the misogyny of the American right-wing is especially interesting: among conservatives the theory circulates that female voters are the main cause for leftist politics and thereby responsible for the squandering of state funds — it being the women who demand social expenditures — although the greatest portion of the US budget goes by far to the Department of Defense. Ghodsee even uncovered a book from 2007 with the title "The Curse of 1920" which maintains that women's suffrage has led to America's downfall, and that salvation was only to be found in its repeal. A tax exemption for working women was not mentioned. The idea that men do things in order to impress women, and that disintegration is imminent without that need, makes a certain horrible sense. In the US election in November it became clear that in the USA the front between left and right also runs between female and male voters.

What has become of the glorified west, since it is permitted to be unashamed of itself without competition from the East?

Ghodsee does not have the solution for the division of society, but she does for the obstruction of the career chances of mothers: more state enterprises. Even in the US, the state is the largest employer, but in Scandinavia it is even larger, and that has a lot to do with real enforcement of equal rights. Only as employer can the state guarantee that female workers are not discriminated against when they become pregnant. In most western countries and in the former Eastern Bloc the number of state jobs has been reduced. Ghodsee does not accept the demonization of all socialistic ideas, for she often refers not to the Eastern Bloc but to Scandinavia, to Germany before the fall of the wall, and Europe before rabid privatization.

24 hour childcare—an outgrowth of capitalism

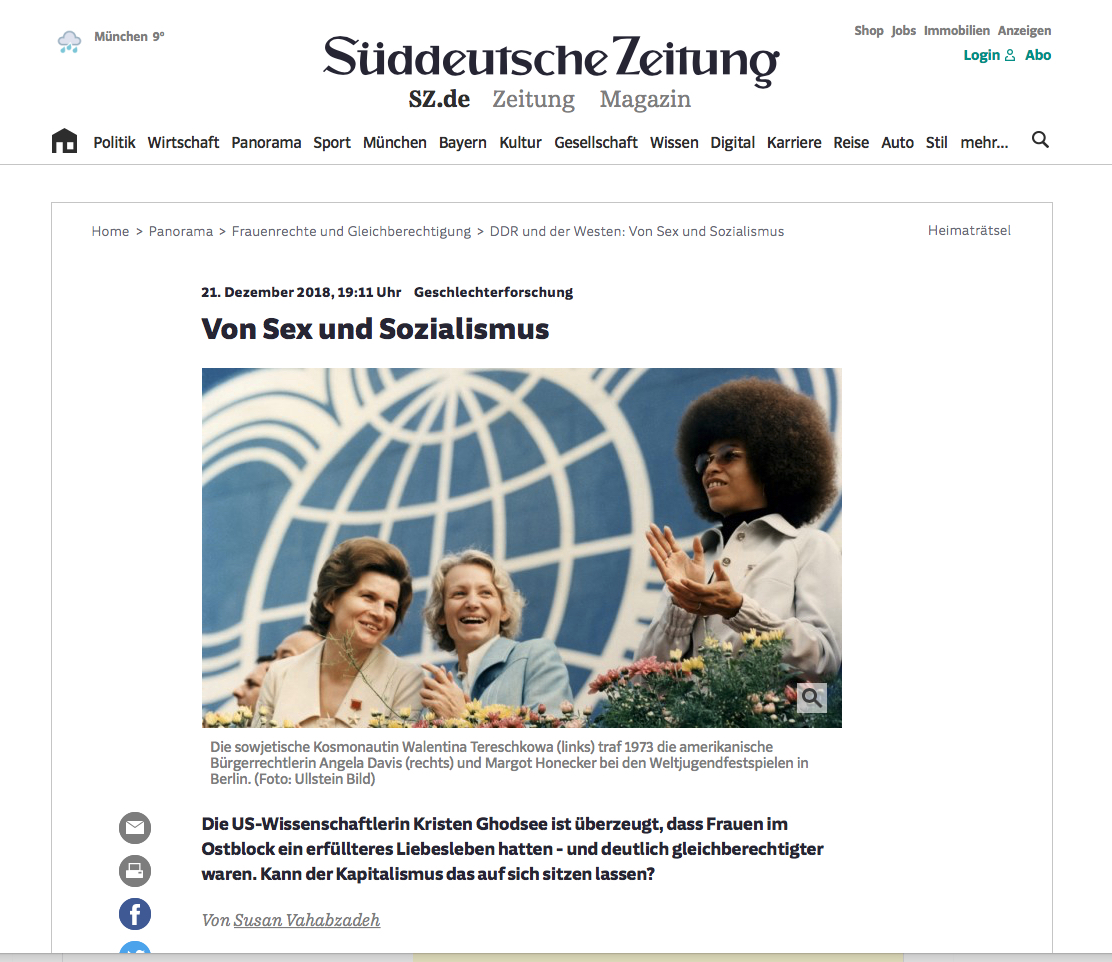

What has become of the glorified west, since it is permitted to be unashamed of itself without competition from the East? That competition enlivened even equal rights, writes Ghodsee: even before the second wave of feminism developed in the USA at the beginning of the 60s, there were state subsidy programs under presidents Eisenhower and Kennedy—out of fear of not keeping pace. The Soviets were ahead on space travel, and the USA feared that they could rely on "double the brainpower". In 1963 Valentina Terschkova flew in space as the first female cosmonaut, a feminist icon of the East, who later posed in Berlin with the American communist Angela Davis. Socialism had the consequence that the proportion of women in technical professions and courses of study rose, and it is to this day higher in the former Eastern Bloc countries than it is in the West.

But the Eastern Bloc bequeathed not only hardcore feminists, female cosmonauts, and female math professors, but also more right wing radicalism. Ghodsee sees this as a symptom of disappointment, paired with anti-communist hysteria, which declares anyone who demands higher salaries to be a secret Ceaucescu fan. It is not entirely fair of her that she exonerates in this regard the same strong state that arranged for equal rights while not once considering the possibility that a totalitarian system could also have bequeathed a lack of fear of autocracy and other enemies of democracy.

For 150 years it was attributed to socialism that it would automatically solve the woman question. That was what Clara Zetkin thought in the 19th century, and she did not want the path of revolution to be stopped because of it. Rosa Luxemburg was also of this opinion. And the revolutionaries who rallied together fifty years ago in universities, saw it similarly–that 1968 was the birth of the second German women's movement; they were rather mistaken.

Of course, the really existing socialism on the other side of the Iron curtain did not resolve and eliminate all questions of women's rights. Kristen Ghodsee knows that too. No socialist state really did anything about violence against women, and the double-burden of women, who had to care for everything having to do with the house (including the children), was the norm. But it is almost the same in capitalism—for one salary only rarely suffices for a family. And when it comes to childcare (which, according to Ghodsee, is rare in the USA and sometimes costs as much as the mother earns): even childcare can become an ugly outgrowth of capitalism. In the USA there are even 24-hour nurseries. For some nurses, who work night shifts, that comes as a relief. However, on the whole such a service represents a system which confiscates the lives of people. In the discussion that Ghodsee wants to initiate, it should not only be about distribution but also about quality-of-life and ethics.

Facebook CEO Sheryl Sandberg appears several times in Ghodsee's book. She is a good example of capitalism producing only a few winners and many losers. Even before Facebook overlooked the Russian interference in the American electoral process, Sandberg should not have been celebrated as a role model, at least not by women. Her "Lean in" theory says that women only need to throw themselves into it—with as much giant ambition and just as free of guilty conscience as men, even at the cost of their private lives—in order to lead large companies. That was always sleazy. To her it was not about solidarity among many women, but about the self-marketing of individual women. Most feminists recognized this, but on American television Sandberg was nonetheless passed around and admired.

However, neither in the Soviet Union at the time, in which almost all women had an occupation, nor today in Scandinavia where equal rights predominate as nowhere else, did women flock into the executive level. Why not? Sandberg is the advocate of a meritocracy. In her representation of woman as executive, neither quality-of-life nor ethics plays a role.

Vanity Fair recently reported about how Sandberg's behavior in things related to Facebook — making democracy-undermining decisions, lying, disappearing— is hardly surprising if one looks at her alma mater: the Harvard business school. Sandberg, who leads one of the world's largest businesses, has no shame trading the privacy of users, downplaying the Cambridge Analytica scandal, and hiring a PR agent in order to blanket George Soros with an anti-semitic campaign.

Very similar things have been taught at the Harvard business school since the 70s. Vanity Fair quotes a story that the HBS Review has published twice: how mountain climbers leave behind a dying old man, without a guilty conscience, because one cannot let oneself be stopped on the way up. That does not sound like the spirit that should shape a society.

If the intertwining of patriarchy and capitalism serves to make men attractive to women, why should women want to function according to the same standards? Perhaps feminism should gradually demand that more than just salaries change — preferably the whole world.