So this actually happened on Thursday last, but because the review was behind a paywall, I was only now able to figure out how to download it using Factiva. I am so grateful to Lynne Segal for her thoughtful and generous review. I am thrilled that people understand the value of revisiting the state socialist past.

The Book of the Day in the UK's Observer!

Meagan Day asked great questions for this Jacobin interview

It’s always a pleasure to talk to such smart and thoughtful journalists. I enjoyed this interview very much.

Interview with Dahlia Balcazar

Thanks to Dahlia Balcazar of Bitch Media for such a fun conversation!

A two-page spread in the UK's Independent!

The gods of publicity have smiled upon me. But I am most grateful to Alison Davies, publicist extraordinaire at Vintage. Link to the electronic version: https://inews.co.uk/news/long-reads/women-sex-gender-pay-gap-capitalism-sexism/

My new column in today's Washington Post

Read the new column here: “What the socialist Kama Sutra tells us about sex behind the Iron Curtain”

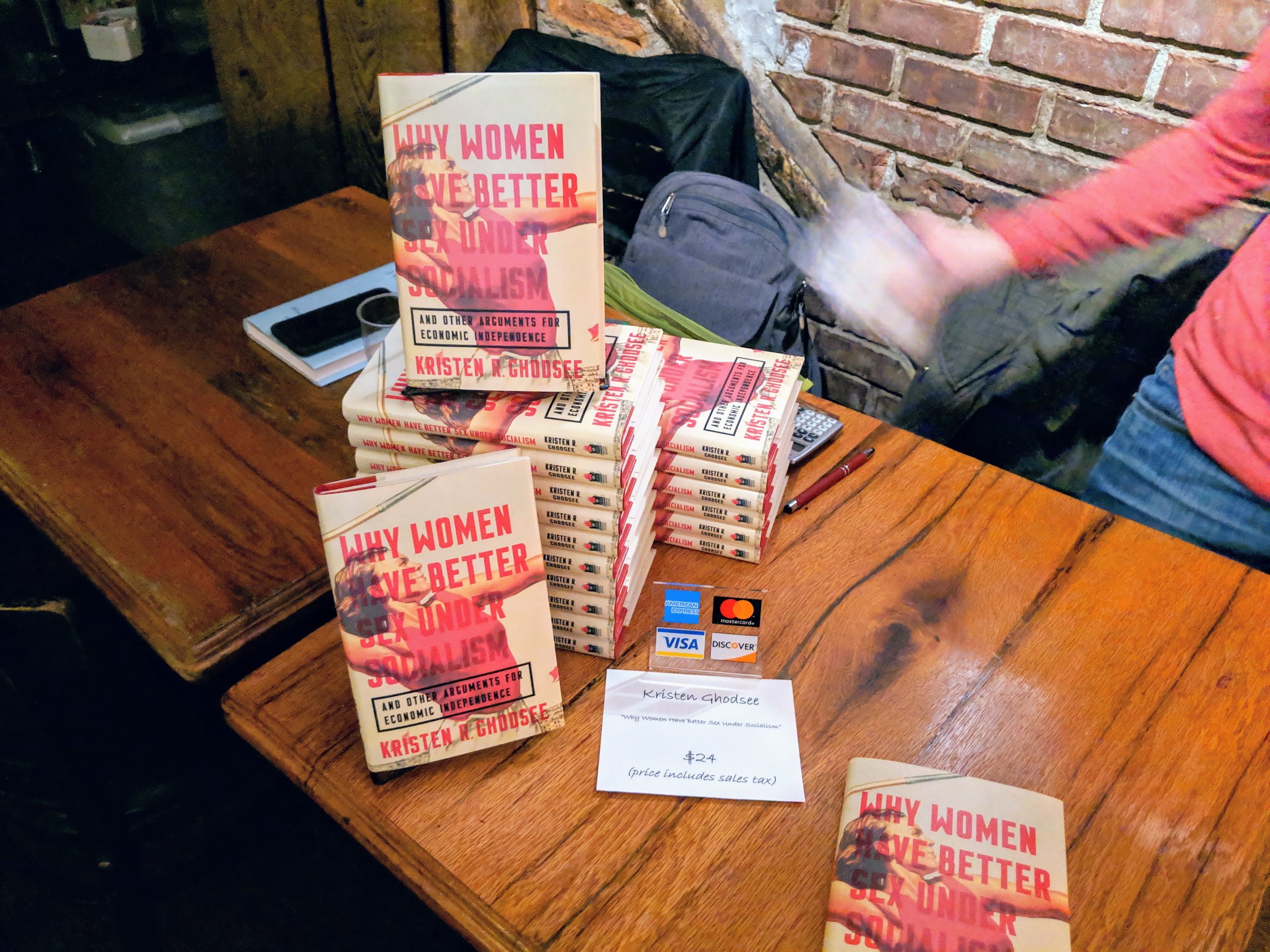

Reviews, reviews everywhere!

The last week has been a whirlwind of reviews to coincide with the original publication date of my book in the US. Perhaps because of Michelle Obama’s memoir, quite a few books were pushed back a week and my new publication date is Tuesday, November 20th, just in time for people to read it before Thanksgiving dinner. It will make for many debates around the table, I am sure. So far the reviews have been very encouraging. Even the conservative Times of London said that parts of the book were “fascinating,” and that “This book is not as silly as its title suggests.” That’s high praise from a Tory paper!

Amazing night at the Half King reading series

Thanks so much to Glenn Raucher for making it happen, and for his astute questions.

What the Pool is reading this week!

“MARISA BATE IS READING… WHY WOMEN HAVE BETTER SEX UNDER SOCIALISM BY KRISTEN R GHODSEE

Thanks to Bernie Sanders and Jeremy Corbyn (in part, at least), the number of young people identifying as socialist is rocketing, and now academic Kristen R Ghodsee is making the feminist argument for some of the policies adopted by socialist states, which, she claims, resulted in women having better sex. The book is born out of a New York Times op-ed she wrote, which points to a study that found women in socialist East Germany had more orgasms than those in capitalist West Germany. As Ghodsee goes on to explore in her book, a government that funds childcare, encourages women into the workforce and supports women into economic independence significantly increases women’s happiness. Ghodsee is an academic, but the tone is accessible and relatable. She’s quick to point out the significant failings of communist states, while illuminating some of the brilliant, but often forgotten, women in and around the socialist movement.

• BUY Why Women Have Better Sex Under Socialism by Kristen R. Ghodsee or pop in to your local bookshop. ”

Two wonderful reviews from The Guardian and Pacific Standard!

Thanks so much to Rebecca Stoner and Emily Witt for their thoughtful reviews in Pacific Standard and The Guardian.

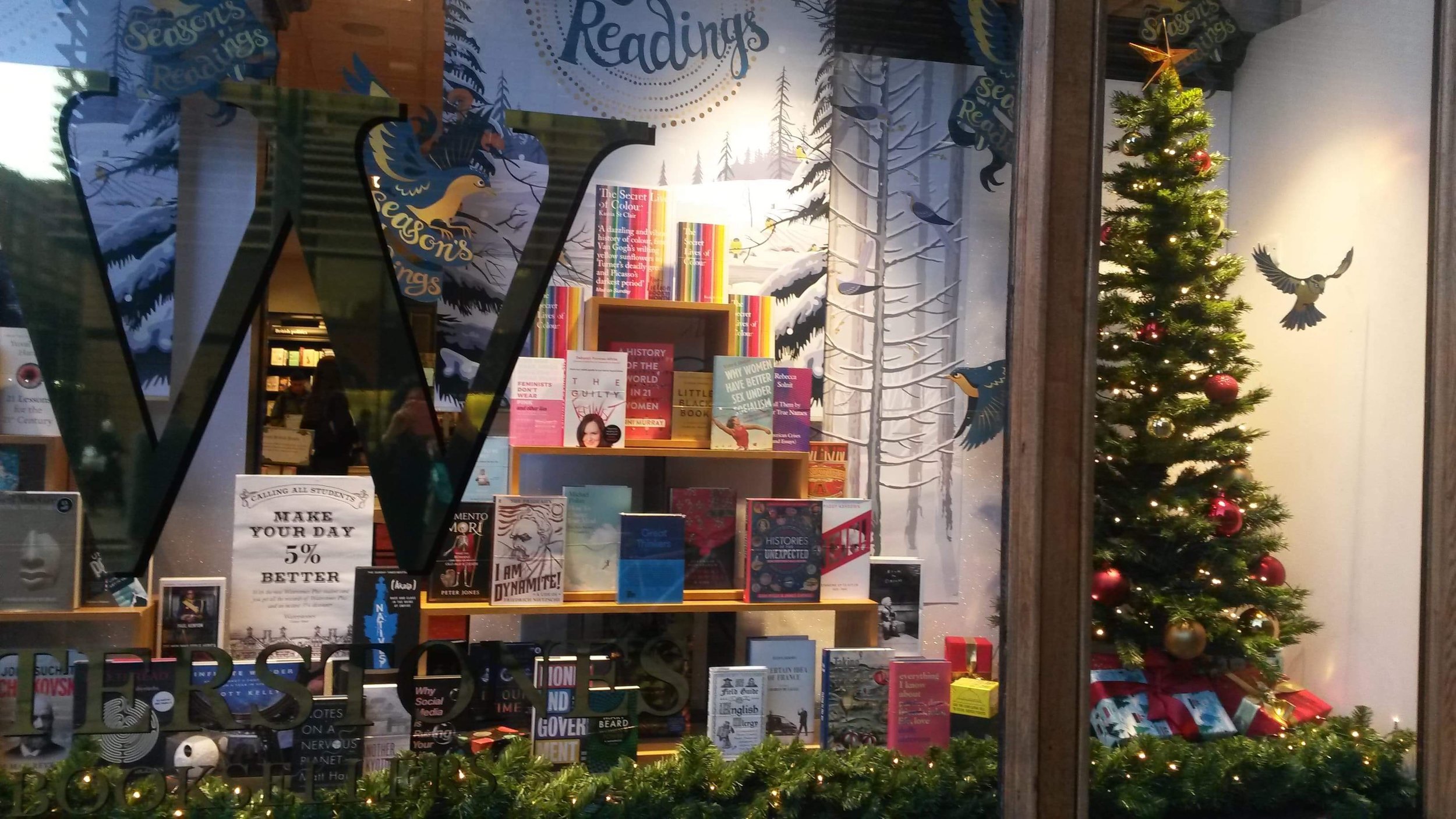

Spotted in the window of Waterstones on Gower Street in London

So thrilled to have chatted with Molly Fischer on The Cut podcast

Thanks to Lidjia Haas and Violet Lucca at the Harper's Blog!

Okay, so I am terribly slow on the uptake because I am not on social media, but I was so thrilled to discover this lovely conversation between Lidjia Haas and Violet Lucca at Harper’s Magazine about Why Women Have Better Sex Under Socialism.

https://soundcloud.com/harpersmagazine/fall-books-and-an-interview-with-rachel-kushner

The conversation starts at around 22:40 and goes for about 10 minutes.

Ok, now I'm convinced...

This helpful table, provide by the White House Council of Economic Advisers (CEA) today, has convinced me finally that socialism would be a terrible idea. We might get health care, education, and public transport, but look how much more we will pay for owning a Ford pickup truck. It’s a slam du(mb)k argument.

https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefings-statements/cea-report-opportunity-costs-socialism/

Kirkus Review →

“From paid maternity leave to employment assurances, an argument for the benefits of socialism for women.

Ghodsee (Russian and East European Studies/Univ. of Pennsylvania; Red Hangover: Legacies of Twentieth-Century Communism, 2017, etc.) sums up her thesis in the introduction: “Unregulated capitalism is bad for women, and if we adopt some ideas from socialism, women will have better lives.” And if you disagree with the author, she clearly doesn’t care. “If you don’t give a whit about women’s lives because you’re a gynophobic right-wing internet troll,” she writes, “save your money and get back to your parents’ basement right now; this isn’t the book for you.” Ghodsee’s in-your-face tone sets the stage for a book that takes readers on a pointed examination of the Soviet experiment. Using her years living in Bulgaria as fodder for the narrative, along with decades of research, she makes the case that there are lessons capitalist countries can and should learn from socialism—e.g., how socialists pushed for equity between men and women and the benefits of collective forms of support for child-rearing. At the same time, the author isn’t blind to the failures of socialist regimes. “Hungarians never managed to redefine traditional gender roles,” she writes, “and domestic patriarchy was strengthened by pro-natalist family policies.” Still, she points to examples of Scandinavian countries where socialist ideas are working to improve women’s lives: “A wider social safety net,” she writes, “like those in the contemporary Northern European countries, will increase rather than decrease personal freedom…no one should have to stay in a job she hates for health insurance, or stick with a partner who beats her because she’s not sure how she’ll feed the kids, or have sex with some sugar elder because she can’t afford textbooks.” Ghodsee makes a convincing case, though she fails to investigate how socialism addresses LGBTQ and people of color. Perhaps she’s saving that for another book.

While the title is the literary version of click-bait, the book is chock-full of hard-hitting real talk.”

Thanks to Jean Bookishthoughts!

So delighted to be included in her September 2018 book haul.

Cover of the Bulgarian version of The Man and Women Intimately

This is one of the Bulgarian covers of a sexual education book that was translated from the German and first published in Bulgaria in 1979.

Summer Reading: The Cold War: A World History

A sweeping history of the Cold War, but Westad doesn't have much to say about women. So far, I've found only one relevant paragraph which segues immediately into a discussion of militarism.

A perfect book for Bassett hounds and history buffs.

“One of the biggest changes throughout the Communist world was in the position of women. All over eastern Europe and eastern Asia the position of women had been governed by patriarchal traditions that gave them little say over resources, work, or family affairs. In areas that had had a taste of capitalism, new opportunities for women were mixed with increased social and economic exploitation. The Communist parties set out to change this sorry state of affairs, and at first many women were able to benefit from the new policies. Access to education, work, and child care improved dramatically in many places. So did women’s control over their own lives. The right to divorce and availability of birth control made for big changes in gender relations. But women were still kept out of political leadership positions, and as the regimes wanted to increase their populations, many women found themselves increasingly caught between work and duties to their families. The dual burden on women turned out to be as troublesome in societies that called themselves socialist as they were in the capitalist countries, and the on-going conflict between progressive ideas and traditional norms at least as intense.”

Summer reading: Axel Honneth, The Idea of Socialism, 2017

Daisy models Axel Honneth's excellent (and short) book, The Idea of Socialism

“For decades, despite a number of attempts at mutual rapprochement, the relationship between the socialist workers movement and the emerging feminist movement remained tense and unhappy. Although it became increasingly clear that women’s liberation not only required greater equality in terms of voting and labor rights, but also a more fundamental cultural change beginning with established forms of socialization if women’s voices were to be freed from the gender stereotypes imposed upon them, the worker’s movement remained blind to such conclusions, clinging instead to the priority of the economic sphere. How different the relationship between socialism and feminism could have been had socialists only been willing to take account of the functional differentiation of modern societies by interpreting the sphere of personal relationships as an independent sphere of social freedom. Had they done so, the moral standard of free cooperation in social attachments based on mutual love soon would have opened their eyes to the fact that the oppression of women begins within the family, where stereotypes are imposed upon them with open or subtle forms of violence, leaving them no chance to explore their own sentiments, desires and interests. The problem, therefore, did not so much consist in involving women equally in economic production, but in granting them authorship of their own self-image, independent of male ascriptions. The struggle for social freedom in the sphere of love, marriage and the family would have primarily meant enabling women to attain as much freedom as possible from economic dependency, violence-based tutelage and one-sided labor within the hatchery of male power. This would enable women to become equal partners in relationships based on mutuality, and it is only on the basis of free and reciprocal affection that both sides would have been capable of emotionally supporting each other and articulating the needs and desires they view as a true expression of their selves.”

“We are unable to anticipate social improvements in the basic structure of contemporary societies because we regard the substance of this structure as being impervious to change, just like things. On this account, the inability to translate widespread outrage at the scandalous distribution of wealth and power into attainable goals is due neither to the disappearance of an actually existing alternative to capitalism, nor to a fundamental shift in our understanding of history, but rather to the predominance of a fetishistic [and fixed] conception of human relations”

Reading Peter Singer on A Darwinian Left

I'm rereading Peter Singer's A Darwinian Left: Politics, Evolution and Cooperation. It's an old book (2000), but I find it a provocative little essay to help rethink the Marxist view of human nature. Can we evolve to be more cooperative? Are Darwinism and Marxism compatible? This is a wonderful little book for discussion groups.